Conference. Echoes of Great Brightness: The Ming Dynasty and Beyond

Echoes of Great Brightness: The Ming Dynasty and Beyond

An International Conference in Honour of Craig Clunas

Time: September 16th and 17th, 2025

Location: Oakeshott Room, Lincoln College, University of Oxford

The Ming period (1368–1644) is central to our understanding of Chinese art, both as the time when many key texts and objects from preceding centuries were edited or curated into the forms in which they have come down to us today, and as the era to which much subsequent artistic practice and discourse has looked back for validation and inspiration. No one would dispute that Professor Craig Clunas pioneered the application of social history to the study of the Ming dynasty and Chinese art history. His innovative methodology has positioned the study of the Ming dynasty as one of the most dynamic and engaging areas in both art history and sinology. With more than a dozen monographs to his name, his international research and publication profile is unparalleled among art historians in the United Kingdom. In 2018, he retired from his position as the Statutory (Distinguished) Professor of Art History at the University of Oxford.

In recognition of his outstanding scholarship, groundbreaking contributions to the field, and his extensive curatorial and academic career, a group of twenty-four scholars are collaborating to present an equal number of papers in the fall of 2025. The conference presentations will address issues and ideas inspired by Professor Clunas’s research, encompassing a wide range of topics, periods, locations, and media—from the Wei-Jin dynasties to twenty-first-century Chinese art, from paintings and prints to teapots and furniture, from gardens and boats to maps and diplomacy, and spanning regions from Jiangnan China to Edo Japan and Europe.

This conference not only honours Professor Craig Clunas but also brings together leading scholars such as Wu Hung, Martin Powers, Richard Vinograd, and Dorothy Ko, thereby drawing significant international attention. In addition to these eminent figures, the event will feature numerous early- and mid-career scholars, providing them with a valuable platform to present their research and cultivate future collaborations within the fields of Ming dynasty studies and Sinology. We are confident that this will be a landmark event in the study of art history, Sinology, and Ming China. All interested parties are warmly invited to attend. As seating is limited, advance online registration will be required.

We very much look forward to welcoming an engaged and enthusiastic audience to the beautiful city of Oxford this autumn.

J.P. Park

June and Simon Li Professor in the History of Art, University of Oxford

Speakers (in alphabetical order):

Katharine Burnett, University of California, Davis

Pedith Chan, Independent Scholar

Huang Xiaofeng, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing

Elizabeth Kindall, University of St. Thomas

Dorothy Ko, Barnard College/Columbia University

Motoyuki Kure, University of Kyoto

Yuhang Li, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Li Ziru, Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts

Liu Lihong, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Liu Yu-jen, National Chengchi University

Luk Yu-ping, British Museum

Quincy Ngan, Yale University

Martin Powers, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Timon Screech, International Research Center for Japanese Studies

Tadahito Tsutsui, University of Kyoto

Wang Cheng-hua, Princeton University

Richard Vinograd, Stanford University

Stephen Whiteman, Courtauld Institute of Art

Aida Yuen Wong, Brandeis University

Winnie Wong, University of California, Berkeley

Wu Hung, University of Chicago

Yin Jinan, Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing

Judith Zeitlin, University of Chicago

SCHEDULE

Day 1: September 16th 2025

8:45–9:15 Registration

9:15–9:20 Welcome I

9:20–9:30 Welcome II

Panel 1: 9:30–10:30

The Empire of Great Brightness: Current Perspectives on the Field

- Martin Powers, “The Persistence of Pattern: Seeking Alternative Paradigms for Cosmopolitan History.”

- Winnie Wong, “Naming a Qing Visual Culture.”

Coffee Break: 10:30–11:00

Panel 2: 11:00–12:30

Mapping East & West: China’s Place in the World

- Yu-jen Liu, “On the Edge of the Canon: The Evaluation of Guiseppe Castiglione in Modern China.”

- Motoyuki Kure, “Arts and Politics in the Diplomat’s Collection: Yakichiro Suma’s Connoisseurship in Modern Chinese and Spanish Paintings.”

- Stephen Whiteman, “Encountering Maps in Early Modern China.”

Lunch Break: 12:30–14:00

Panel 3: 14:00–15:30

Fruitful Sites: Urban Centers and Governance in East Asian Art

- Cheng-hua Wang, “Imagined Cities and Imperial Territoriality at the Court of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736–1795).”

- Pedith Pui Chan, “Remembering and Reimagining Jiangnan in Southwest China during the Second Sino-Japanese War.”

- Timon Screech, “First Steps Towards a Cultural History of the Rokuhara District of Kyoto.”

Tea Break: 15:30–16:00

Panel 4: 16:00–17:30

Material or Spiritual: The Interplay of Tangible and Intangible in Chinese Art

- Luk Yu-ping, “Mounting and Mending: Traces of Borders and Early Conservation Work on Dunhuang Portable Paintings and Banners.”

- Dorothy Ko, “In Search of the ‘Spirit of Artisans’ in Early Modern and Modern China.”

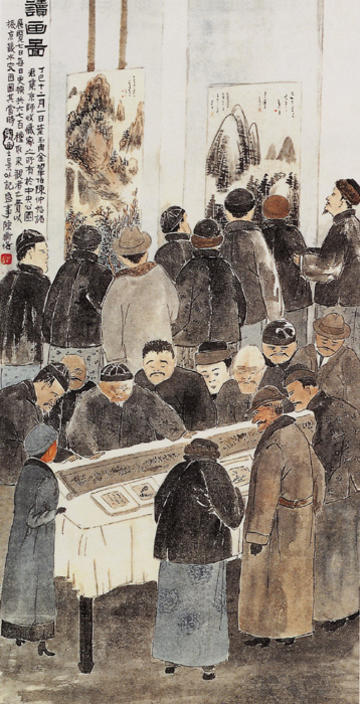

- Aida Yuen Wong, “Elegant Gatherings and Cultural Ambivalence in Colonial Taiwan.”

Dinner: Presenters Only

Day 2: September 17th 2025

9:00–9:15 Registration

Panel 1: 9:15–10:45

Spectral Mediums: Reproducing the Past in East Asian Art

- Judith Zeitlin, “The Strange Reimagined: Illustrating Liaozhai Tales in Different Mediums.”

- Tadahito Tsutsui, “Ming Dynasty Printed Books and the Emergence of Early Ukiyo-e.”

- Quincy Ngan, “Looking Back, Looking Forward: Color in Chinese Art Historiography.”

Coffee Break: 10:45–11:00

Panel 2: 11:00–12:30

The Art of Being Seen: Portraiture, Beauty, and Cultural Memory in Chinese Painting

- Huang Xiaofeng, “Fictionalizing Real Faces: Cultural Constructs in the Portraiture Album of Ming Eminent Men”

- Wu Hung, “Leng Mei (c. 1662–1721) and the New Mode of ‘Beauty Reading’ Paintings.”

- Ziru Li, “The Dissemination of the Nine Horses schema and the Conceptualization of Ren Renfa’s Canonicity in Art Historiography.”

Lunch Break: 12:30–13:45

Panel 3: 13:45–15:15

Flowing Visions: Landscape, Travel, and Spatial Imagination in Ming Art

- Lihong Liu, “Delineating the Stream: The Riverine Aesthetic in the Art of Ming China.”

- Yin Jinan, “《扬士奇的江河湖海》: 一个明代首辅的视觉之旅”

- Elizabeth Kindall, “Persona and Space in an Unbound Album of Parting Paintings.”

Tea Break: 15:15–15:30

Panel 4: 15:30–17:00

Superfluous Things: The Production, Consumption, and Representation of Objects in Early Modern China

- Katharine Burnett, “Chen Jiru, Shi Dabin, and the Marvelously Extraordinary, Inventively Original Teapot.”

- Richard Vinograd, “Set Pieces: Media, Matching, and Materiality in Illustrations of Jin Ping Mei.”

- Yuhang Li, “Fluid Transcendence: Commemorating Time Through Boats and Water.”

Break: 17:00–17:15

Introduction of Craig Clunas: 17:15–17:30

Keynote speech: 17:30–18:15

Craig Clunas, “Should Ming painting make us sad?”

Reception: 18:15–19:15 (Open to all participants and audience)

Conference Dinner: 19:15 (by Invitation Only)

Day 3: September 18th 2025

Optional: The Viewing of the Backhouse Collection: 10:00–12:00

The Horton Room, Weston Library

Paper Abstracts (in alphabetical order of presenters’ last names)

Katharine Burnett

“Chen Jiru, Shi Dabin, and the Marvelously Extraordinary, Inventively Original Teapot”

Zisha (purple clay) teapots made at the pottery town of Yixing in Jiangsu Province have long been prized by tea connoisseurs for their flavor enhancing characteristics and their inventive shapes. The inventiveness of the shapes, formative in the late Ming, have become if not commonplace, commonly accepted as a norm for Yixing ceramics. While the tradition of potting in Yixing is millennia old, it was only in the mid-Ming that potters first began to create pots in inventive shapes; this inventiveness really took off and came to full fruition in the late Ming. The question is: Why? This paper looks at specific examples of late Ming teapots, contemporaneous art theory, and the known relationships between major potters (commoners) and art theorists (the intellectual elite) to help us better understand how ideas could have mixed between social groups, and how major aesthetic values of the day might have affected tea ware production.

Pedith Pui Chan

“Remembering and Reimagining Jiangnan in Southwest China during the Second Sino-Japanese War”

Jiangnan has historically served as a cultural and economic hub of China with considerable impact on artistic production. Its distinctive natural scenery has cultivated specific landscape aesthetics that have defined Chinese art. During the Nanjing decade (1927–1937), the Nationalist government initiated the Southeastern Tours project to develop transportation infrastructure, tourism, and scenic sites in the region, thereby incorporating Jiangnan into representations of the national landscape. However, the onset of the Sino-Japanese War catalysed the cultural center’s shift to the southwest inland, where displaced artists toured the exotic wilderness of southwest China. This paper explores the discourse of Jiangnan and its role in shaping representations of the national landscape during wartime China, uncovering the multi-layered sociocultural meanings embedded in the textual, visual, and spatial representations of Jiangnan in modern China. Wartime periods provided complex sociocultural contexts that shaped artists’ perceptions of southwest landscapes. Building upon the landscape aesthetics of Jiangnan, new scenic sites were constructed and promoted by the government. Despite cultural leaders’ critiques of this aesthetic as overly feminine and in need of alteration to suit wartime exigencies, Jiangnan’s landscapes continued to be memorised and imagined by artists and writers who encountered and redefined the picturesque landscapes of southwest China.

Huang Xiaofeng

“Fictionalizing Real Faces: Cultural Constructs in the Portraiture Album of Ming Eminent Men”

Portrait painting flourished during the Ming Dynasty, producing many exquisite works that have become essential sources for art historians and scholars. These portraits are often examined in the contexts of ancestral worship rituals, the influence of European visual traditions, or efforts to reconstruct the tangible appearances of historical figures. Among them, the Album of Ming Dynasty Portraits (Mingren xiaoxiang ce), housed in the Nanjing Museum, consists of twelve leaves believed to depict officials and literati from the Jiangsu-Zhejiang region during the Wanli and Tianqi reigns. The album features prominent late-Ming cultural and artistic figures such as Li Rihua and Xu Wei. Recently uncovered records indicate that the Shanghai Museum also holds a strikingly similar album. However, the identities of these portraits’ subjects were retrospectively assigned by early 20th-century collectors, with no reliable contemporaneous evidence to support these attributions—casting considerable doubt on their authenticity. This paper challenges these claims, proposing that these bust-style portraits may not depict the presumed historical figures at all. Instead, they could be fictionalized representations, possibly created as promotional showcases by portrait workshops.

Elizabeth Kindall

“Persona and Space in an Unbound Album of Parting Paintings”

How did viewers physically interact with unbound painting albums prepared as parting gifts? I explore how viewers of the 1583 Album for Li Yi constructed persona and space through their physical interaction with this unbound album. Created as a parting gift for the Suzhou official Li Yi, sixteen of its leaves are paintings that illustrate identifiable sites in the south, such as waterscapes and mountainscapes. Each also has a companion leaf of poetry written about the site. While each painting or poem could be read on its own or as part of its pair, my close examination of Album for Li Yi shows underlying connections between all the folios and how they worked together to meet the sociocultural agenda of the coordinators. I will first examine how albums produced a public space that afforded coordinators and participants opportunities to perform the ceremonial parting behaviors they could not achieve in real life. I will then explore how the coordinators of the album orchestrated a persona that was activated when the entirety of the album was laid out on tables.

Dorothy Ko

“In Search of the ‘Spirit of Artisans’ in Early Modern and Modern China”

In his book The Religious Ethic and Mercantile Spirit in Early Modern China, historian Yü Ying-shih revises Max Weber by arguing that Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism in early modern China were conducive to the development of a capitalist work ethic, and that one can discern this ‘mercantile spirit’ in the life and deeds of merchants detailed in their epitaphs. Taking this argument as a point of departure, this paper asks two further questions. First, did artisans share the merchant’s spirit, or did craft workers forge a distinct ‘spirit of artisans’? Second, did domestic women, in their everyday practices of nühong /nügong (womanly work,) partake in this ‘spiritual significance of labor’? In shifting attention from merchants to artisans and women—actual producers of myriad goods and commodities—we highlight the importance of embodied skills and handwork in sustaining political and social life before the machine age. In this way, this paper begins and ends with a question: What is the meaning of craft, and what role should it play in modern life?

Motoyuki Kure

“Arts and Politics in the Diplomat’s Collection: Yakichiro Suma’s Connoisseurship in Modern Chinese and Spanish Paintings”

Yakichiro Suma (1892–1970), a Japanese diplomat during the Showa period, is well known as one of the first collectors of Qi Baishi (1864–1957), a master of modern Chinese ink painting. Suma was dispatched to China in the 1930s, prior to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and later to Spain during World War II. As a “literati,” a diplomatic bureaucrat with a deep appreciation for art, he collected numerous artworks in both China and Spain. These collections are now housed in the Kyoto National Museum and Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum.

Suma employed the artworks in his collection as tools for diplomatic negotiations with the Wang Qingwei administration in China and the Franco administration in Spain. His unique connoisseurship is admired in both diplomatic circles; he recognized a “naivety” in the paintings of Qi Baishi and José Gutiérrez Solana (1886–1945), highlighting the commonalities between Eastern and Western art. This paper examines Suma’s connoisseurship of modern Chinese and Spanish paintings to reveal how a Japanese diplomat sought to bridge art and politics in China and Spain during the first half of the twentieth century.

Yuhang Li

“Fluid Transcendence: Commemorating Time Through Boats and Water”

In both Buddhist and Daoist practice, a boat or a ferry refers to its infinite capacity to transport all sentient beings to cross the sea between the living and the dead, and is used to explain the idea of universal transcendence. Such doctrinal concepts were often illustrated in religious prints and murals. In the late Qing period, however, Empress Dowager Cixi (1835–1908), the de facto ruler of late Qing China (1840–1911), began to evoke the meaning of such transcendence through actual boats and to incorporate boating on water as part of the visual and material practice of birthday celebrations. This paper rethinks water, or more specifically lakes in imperial gardens, as a site for the construction of religious experience. By discussing how the material forms of the boats made in various media and the act of boating, this paper explores how a female monarch practiced mimesis to transport herself into a religious realm through the creation of spectacles and how she sought her own immortality through her birthday celebrations.

Ziru Li

“The Dissemination of the Nine Horses schema and the Conceptualization of Ren Renfa’s Canonicity in Art Historiography”

The Victoria and Albert Museum’s Yuan-dynasty Feeding Horses (attributed to Ren Renfa) replicates a mirrored section of the Nelson-Atkins Museum’s Nine Horses, epitomizing the proliferating “Nine Horses” schema tied to Ren. While similar schema and works underpin modern studies of Yuan horse painting, authenticated Ren pieces remain scarce. By the Ming dynasty, the schema was systematically replicated across social strata via printmaking and exact copies, often misattributed to Li Gonglin or Zhao Mengfu to amplify canonical authority. Concurrently, Ren-attributed works entered Japan as aristocratic collectibles, spurring localized reinterpretations. Divergent Sino-Japanese interpretations of Ren’s artistry emerged from distinct painterly epistemologies, a schism intensified by 19th-century photomechanical reproduction and Euro-American acquisitions of Sino-Japanese art. Tracing the schema’s transnational circulation, this study examines how image dissemination, epistemic frameworks, and viewer reception collectively construct—and destabilize—art-historical taxonomies, deconstructing the artificial mechanisms of artistic canon formation.

Lihong Liu

“Delineating the Stream: The Riverine Aesthetic in the Art of Ming China”

One day in autumn 1489, when Wen Zhengming (1470–1559) was just beginning to learn painting from Shen Zhou (1427–1509), Shen demonstrated how to paint “Ten Thousand Li of the Yangtze River” (Changjiang wanli tu ). At that time, the twenty-year-old Wen had just passed his county-level examination to become a government student. However, many years later, after he became a famous painter, it was this painting and that story that he recalled. Why did Wen recall that story and that painting? This talk reveals that the riverine and riparian landscapes of the Yangtze persisted in Chinese landscape painting not only as subject matter but also as an aesthetic mode and impetus for art historiography. I argue that the river system, as a political realm and a hydro-social landscape, facilitated literati engagement with the material world and inspired their artistic creation. They aspired to channel and change the waterways as a fundamental part of their political ideology of governance, self-image, and artistic lineage.

Yu-jen Liu

“On the Edge of the Canon: The Evaluation of Giuseppe Castiglione in Modern China”

Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining, 1688–1766), the Milan-born Jesuit painter serving at the Qing court, has attracted ambivalent views since the first half of the twentieth century, at the time when a modern story of ‘Chinese art’ emerged. Despite working for the Qing emperors for more than half a century, Castiglione’s European origin and art training, as well as his ‘hybrid’ style, have tended to result in his being edged out of the Chinese art canon. Nevertheless, the numerous works he left in the former Qing imperial collection ensure his public visibility in the museum environment. This paper examines the conflicting views and attitudes on Castiglione expressed during the Republican period by artists, theorists and art historians of various backgrounds and stances, as well as his representation in popular culture. In the hope of understanding the mechanism of art evaluation for past Chinese art in modern times, this paper aims to see how these views from different positions developed into standard sets of opinions about Castiglione ready for later mobilisation, and how they might clash with one another at different levels, thus leaving the appraisal of Castiglione permanently unsettled.

Luk Yu-ping

“Mounting and Mending: Traces of Borders and Early Conservation Work on Dunhuang Portable Paintings and Banners”

Research on Dunhuang portable paintings and banners from the so-called ‘Library Cave’ (Cave 17), Mogao Caves, Dunhuang, tend to focus on images depicted on them rather than their construction as material objects. Yet, these paintings are stitched together with pieces of silk or hemp fabric, and often have textile borders that protected them or supported their display. These borders may have been separated from their central panels because of later conservation work. Some paintings have fragments of paper, reused from manuscripts, that have been pasted on to their reverse to mend points of weakness. This paper examines examples of these processes of production and modifications to consider early conservation and mounting practices at Dunhuang and what they may reveal about these paintings and banners as material objects.

Quincy Ngan

“Looking Back, Looking Forward: Color in Chinese Art Historiography”

Over the past few decades, studies in Chinese art have revealed the multivalent significance of color in textiles, ceramics, bronzes, culture, history, and philosophy. In this historiography, ancient and medieval China are often conceived as the heyday of Chinese civilization with Ming and Qing being the shadow of this cultural prosperity. This paper seeks to reframe Ming and Qing as a forward-looking, early modern period in the long-term development of color’s usage. Divided into three parts, this paper first reflects on the needs and broader issues within the field by introducing recent studies, highlighting different approaches, scholarly interests, and the potential of incorporating scientific analysis in art-historical research. The second part examines how studies on Chinese painting color differ from and align with other mediums of Chinese art and the broader discipline of art history. The last part delves into Ming and Qing paintings within the context of early modernity, analyzing artworks, painting treatises, and other textual records. The juxtaposition of historical discourse on color with existing scholarship challenges established literati biases in the historiography of Chinese painting and refutes the persistent assumption of stagnation in the cultural history of color during the few centuries in question.

Martin Powers

“The Persistence of Pattern: Seeking Alternative Paradigms for Cosmopolitan History”

In “Sinicizing Early Modernity” David Porter suggested that, for Hegel and other European apologists, “writing China out of history was an act of instrumental amnesia: a deliberate occlusion of rival claimants to exemplarity, and of the memory of a more truly cosmopolitan early modern past.” From the late Twentieth century until today, Craig Clunas has ranked among the most articulate and thoughtful exponents of a more cosmopolitan history of the modern era. Having grown up during the last Cold War, he contributed persuasively to the development of a more culturally integrated history of art. That development peaked in the early years of this century, but now a second Cold War has erased much of whatever was gained. What are our options? This paper examines the visualization of “China” over roughly a century. Despite the rich variety of imagery, most images were built from a limited number of scaffoldings, or paradigms. Some scaffoldings could support a cosmopolitan history of art; most cannot. Let us see if we can discover where the differences lie.

Timon Screech

“First Steps Towards a Cultural History of the Rokuhara District of Kyoto”

This paper is the first foray into a projected book-length study of Rokuhara. Although the placename has mostly fallen from use, Rokuhara was once the key district of Kyoto or rather of just outside it. Kyoto was established on a green-field site in 794 with ten east/west avenues, all abutting the River Kamo to the east. The city was established with two rules: it was to have no privately-endowed temples and no warrior residences.

A little community called Rokuhara (‘six fields’) lay across the river between Fifth and Sixth venues, in the mid-city area, so easily accessed from Kyoto proper. This soon became site of many temples, and a Fifth Avenue bridge was added to ease passage. Temples meant graves, which imparted a somewhat wistful, if not lugubrious aura to the place, as smoke rose up from funeral pyres. For warrior residences, the Taira clan took possession of a swathe of the area, and when they were obliterated, the first shogunate set up its Kyoto base here.

Tadahito Tsutsui

“Ming Dynasty Printed Books and the Emergence of Early Ukiyo-e”

The ways societies react to new cultural forms can vary widely. As trade routes expanded in the 17th century, various countries around the world began importing printed books from China. However, the types of books imported, the social classes that had access to them, and people’s responses to Chinese culture differed significantly. In 17th-century Japan, with its long history of contact with Chinese culture, the imported classical Confucian and historical texts elicited little reaction. However, the Japanese of this time were fascinated by the illustrations appearing in illustrated printed books intended for the general public, which emerged from the early modern consumer society of the Ming dynasty. Their expressive style became an important inspiration for the imagery of the early ukiyo-e prints that were beginning to flourish in Japan. That said, the adoption of popular illustrations from Ming-era printed books and their incorporation into popular ukiyo-e prints was not a straightforward process. Instead, the intellectual classes of Japan played a mediating role in this cultural transmission. This presentation will clarify the specific ways in which the imagery appearing in Ming-era printed books was received in Japan and how it influenced later artistic developments. By doing so, I will explore the issue of cultural mobility across social classes.

Cheng-hua Wang

“Imagined Cities and Imperial Territoriality at the Court of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736–1795)”

At the Qianlong court, by restructuring traditional categories of paintings associated with landscapes and/or figures and introducing new modes of pictorial representation, court images transformed the land and people into manifestations of territorial domination and imperial authority. These pictures were so diverse as to include route maps, city views, ethnographic images, battle scenes, pictorial records of imperial tours, and various kinds of works that can generally be subsumed under the label of “landscape.” Many of these pictorial themes and modes were not unprecedented, but the Qianlong examples formulated new signified fields that conveyed the sense of territorial authority. The research in the present study employs the concept of territoriality to explore the position of cityscapes in Qianlong’s politics of visualizing territory through an examination of three paintings depicting imagined cities.

By “territoriality,” I refer to the emperor’s political agenda of reifying the vast territory under his reign through different types and levels of visual representation. To quote Chandra Mukerji’s theory, territoriality is not only “a way of feeling about a portion of land” but also “a form of material practice,” which, in the context of this research, refers to the production and viewing of the paintings that manifested the land and/or people under Qing rule, both real and symbolic. The so-called “Qing territory” was not necessarily an empirical and given fact but something that required constant characterization, codification, and endorsement to assume a role capable of bolstering the Heavenly Mandate. The paintings at issue, two of which are based on Qianlong’s poems, inform the emperor’s approaches to land and people, represent the imperial enterprise of territory, and construct what “Qing territory” signifies. They also reveal power relations between the viewer and the depicted scenes, the central authority represented by the emperor and local places, and among the different places and spatial units seen in them.

Richard Vinograd

“Set Pieces: Media, Matching, and Materiality in Illustrations of Jin Ping Mei”

This paper will explore some complex relations between textual narratives, woodblock print illustrations and album painting illustrations of the late Ming novel Jin Ping Mei, focusing on the 200-episode set of print illustrations in the Chongzhen period (1628–1644) edition of the novel and a corresponding but now dispersed illustration project of album paintings likely sponsored by the Kangxi-era (1661–1722) imperial court. The translations between monochrome prints and painting media present questions of authorship, originality, and illustrative strategies. The most conspicuous alterations in the paintings, which are highly but not entirely derivative of the prints, are the profligate depictions of vibrantly colored and patterned objects to accompany the figural narratives: embroidered and brocaded textiles and figured carpets, lacquered bowls and columns, gold vessels and jewelry, ornately festooned and painted lanterns, patterned marbles, and inlaid screens among many other types.

The album paintings often depict hypermaterial, visually and spatially intensified environments that offer analogues for domestic, social, and psychosexual interactions within patterned but at times disorienting interiors. Throughout the narratives and illustrations of Jin Ping Mei, things, and people take part in complex orchestrations of display and hiding, observation and obscuration. Amid the kaleidoscopic arrays, possibilities of confusion and dissimulation are ever-present.

Stephen Whiteman

“Encountering Maps in Early Modern China”

Early modern China experienced a significant expansion of geographic knowledge, in terms of both its quantity and detail, and in its availability and dissemination. Maps shaped and were shaped by changing perceptions of space within China, and China’s place in the world. From manuscripts to books, sheet prints to fans, and much more besides, the material record shows that maps were everywhere. But how and where were they encountered? How did they circulate? How were they looked at and used, and what did people have to say about them? This paper explores material encounters with a range of cartographic objects in order to rethink the place of maps and mapping in relation to broader visual and spatial cultures, particularly those of print and the book, in early modern China.

Aida Yuen Wong

“Elegant Gatherings and Cultural Ambivalence in Colonial Taiwan”

During the Japanese colonial period in Taiwan (1895–1945), literati-style gatherings became vibrant arenas where Japanese officials and Han Taiwanese gentry engaged in traditional practices of poetry, painting, and calligraphy. Promoted under the ideology of “same language, same script” (dōbun dōji), these “elegant gatherings” (yaji) were encouraged by the colonial regime as tools of cultural assimilation and elite co-optation. Japanese participants sought to legitimize their presence and authority by embedding themselves within local cultural milieux, aiming to cultivate a class of aesthetically refined and politically compliant subjects. For Han Taiwanese participants, however, the stakes were more complex. Participation offered access to social prestige under a new regime, yet also became a subtle means of preserving classical Chinese cultural identity and asserting intellectual continuity. This paper explores these gatherings as spaces for literati arts and political bargaining. It re-centers a phenomenon long marginalized in modern Taiwan’s art history, revealing how artistic production operated not only as cultural expression, but also as a contested mechanism of power and belonging under colonial rule.

Winnie Wong

“Naming a Qing Visual Culture”

The oeuvre of Craig Clunas is remarkable for broadening our understanding of Chinese Art as part of the historical past more generally and the visual expanses of the Ming more specifically. By questioning canonical definitions and categories through social history, through deep readings of aesthetic texts, and through bringing material and visual culture into conversation with literati art, Clunas’s scholarship has tirelessly questioned elite forms of exclusion that impinge upon how we pursue our understanding of the past today. In standard historiography, the Qing merely follows in the Ming, with allowances to be made to account for Manchu political rule and European interactions. But if we were to follow Clunas’s account of Ming visual culture––with all the aesthetic nuances and component social parts that he has described, alongside his questioning of hardened habits of thinking, how would we delineate a Qing visual culture? Would there be such a thing as a Qing visual culture? Would it be “Chinese” in the senses he has troubled? Would it be bounded by the visual?

Wu Hung

“Leng Mei (c. 1662–1721) and the New Mode of ‘Beauty Reading’ Paintings”

The “Beauty Reading” painting (jiaren dushu tu) was a popular subgenre of “Beautiful Women Painting” (shinü hua or meiren hua) during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties. Its emergence reflected the rising influence of women’s literacy and courtesan culture, as well as the growing importance of literary refinement as a criterion for evaluating feminine accomplishment. Early examples of this genre emphasized the act of reading rather than the content of the books. However, a group of works from the early 18th century introduced a new focus, meticulously depicting the texts, annotations, and page layouts of the books held by the female figures.

By examining the content, style, authorship, and historical context of these works, this paper argues that they were created by the Qing court painter Leng Mei. This innovative style combined portrait composition with elements of European painting techniques and represent a new mode of “Beautiful Women Painting” that emerged around 1720.

Yin Jinan

“《扬士奇的江河湖海》: 一个明代首辅的视觉之旅”

作为经历过明朝前期洪武,建文、永乐、洪熙、宣德和正统六位皇帝统治时期的明代文官扬士奇,政治生命漫长,既是江西文官集团的政治领袖,也宫廷台阁文学的文坛领袖,他本人收藏古籍,刻帖碑拓,古代的书法和绘画,看过其他人的收藏,为当时的文宫和贵族写有大量题跋。他与当时的宫廷画家高度互动。早年游历长江,湘江,衡山,在武昌生活十年,曾经两次往返于京杭大运河,观看过两岸的古迹和友人,一生长期居住在南京和北京。既看到了南洋的贡品,也看到了中国古代传统意义上的祥瑞。杨士奇早年因为避祸有三年的经历在他的年谱中处于空白状态,经过我的研究全部复原出来。也实地走访了他去过的地方。本文通过大量材料讨论杨士奇个人关于自然山川,政治地理,历史景观,他那个时代的当代艺术和文学之间的视觉经验和图文关系。

Judith Zeitlin

“The Strange Reimagined: Illustrating Liaozhai Tales in Different Mediums”

Pu Songling’s (1640–1715) masterpiece, Liaozhai’s Strange Tales (Liaozhai zhiyi) was not published until fifty years after his death, whereupon it became a major hit. Woodblock imprints of tale and anecdote collections in Classical Chinese, unlike other genres of fiction and drama, were not typically illustrated; the first published edition of Liaozhai and the many subsequent annotated editions over the next century were no exception. This changed in the later nineteenth century with the introduction of lithographic printing technology, and the publication of a fully illustrated edition with poetic captions (Xiangzhu Liaozhai tuyong , 1866), which subsequently inspired pictorial reworkings of these illustrations in other mediums from hand-painted albums to reverse glass painting. The lithographic edition is credited with launching the vogue for visual renditions of Liaozhai tales, but many chapters of a completely independent large scale multivolume lavishly painted album called Liaozhai quantu have recently been rediscovered scattered in two European libraries (Vienna and Geneva). This striking, deluxe album is undated but probably dates from the nineteenth century. Twentieth- century ink painters, such as Pu Ru (Xinyu) (1896–1963) and contemporary artists such as Peng Wei (b. 1974) have gone further in imagining playful new modes of illustrating Liaozhai. Rather than conducting a survey or history, this paper will focus on close readings of several key illustrated stories to see how the core Liaozhai theme of the strange was transposed into different visual mediums and reinterpreted in different artistic idioms from the nineteenth into the twenty-first century.