The Laurence Binyon Prize: Northern Vietnam, 17th - 30th July 2025

The Laurence Binyon Prize: Northern Vietnam, 17th - 30th July 2025

By Tom Greany, History and English

I applied to the Laurence Binyon Prize with the intention of visiting an international art expo in Vietnam, exploring the country’s vibrant street-photography scene, and composing a portfolio of my own photos to be exhibited in Oxford on my return. I pitched my project to Jericho’s clear-eyed culture hub, Common Ground Café, during their exhibition submission window in the spring, and they kindly agreed to take on the project. I was able to actualise a good deal of this plan and much more in between, but as ever with these things, itineraries were buffeted by contingency and crazy weather, now the subject of a lengthy Wikipedia article on Storm Wipha.

I touched down in Hanoi on the evening of the 17th of July, and was immediately met by a flood of notifications issuing weather warnings for the next day. Rain is to be expected in mid-summer, deep in the country’s monsoon season, but the storm which rushed into the capital a day later was neither typical nor trivial. That day, a tourist boat capsized off the country’s North Coast, in the Gulf of Tonkin, tragically killing thirty-nine passengers. As I made my pilgrimage to the Temple of Literature in the city-centre that same afternoon, the typhoon materialized in an instant, and within minutes I was huddling in a bathroom with water up to my ankles as trees came crashing down outside. A national emergency was declared. Needless to say, such severe weather forced me to map out a new trajectory for my trip.

Firstly, and distressingly, the art expo I had planned to visit in late July (and the reason for my travelling in the rain season, rather than at a more sensible time) was cancelled, and rescheduled for later in the year. Secondly, flooding and storms were so severe south of Hanoi that, rather than venturing down the coast as I had originally planned, I was forced to do an about-turn and head north towards the mountainous Chinese border, which I had heard was suffering less from the weather.

As circumstance contrived what seemed like a tailor-made plot to hamstring my original project, I decided to draw up a new plan that would allow me to make the most of the trip and make good on the promises of my application. I drew up a list of all the independent photography galleries and museums I would be able to visit on the trip, bought a filter for my camera that would pick apart the myriad greys I was encountering, and planned out a route that would work with, rather than against the storm. I surrendered to the beast! And there, in an instant, was a well-wrought scheme to unify the photographs I produced over the next two weeks. This became a documentary project, and one much more cohesive than I had planned. Rather than I hopping between famous cities as I pleased, I would have to cling to Virgil’s tails as I made my way along the northern coast with no tourist infrastructure, the threat of a once-in-a-generation typhoon looming, and a film camera from 2002 whose components were worryingly exposed to the elements.

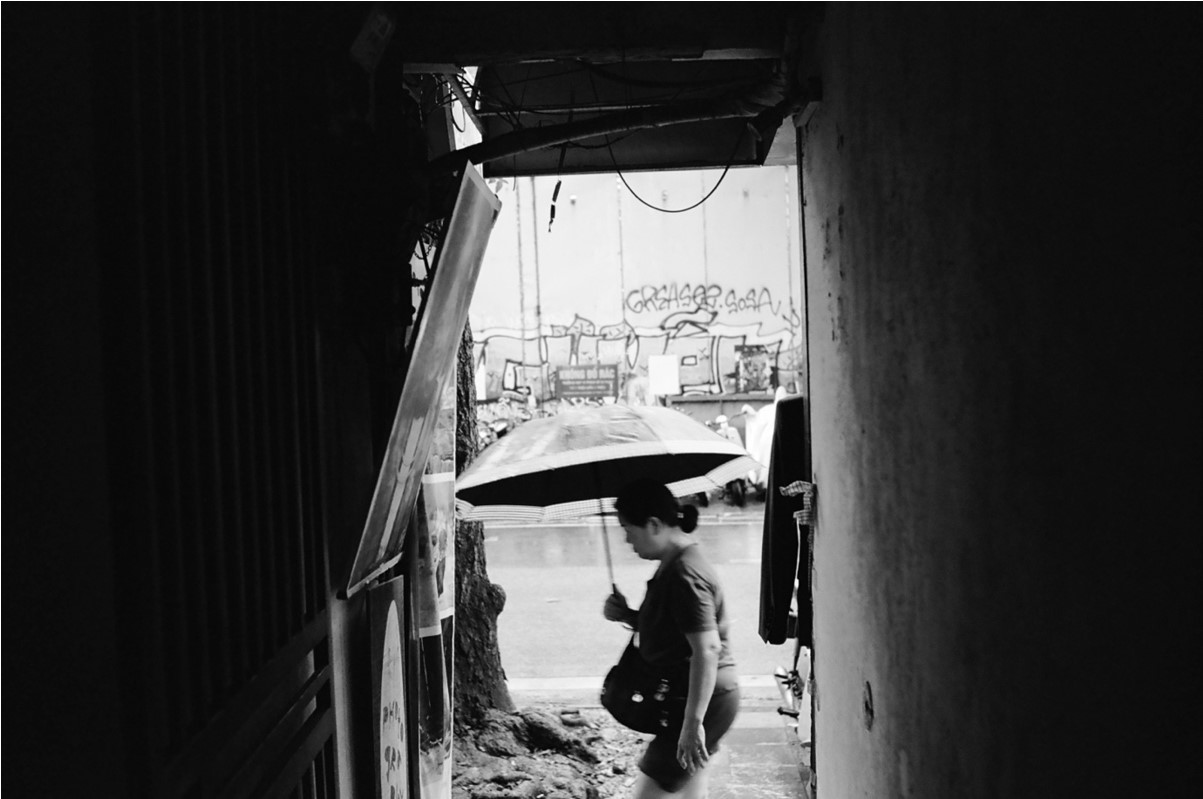

The first few days in Hanoi, though rain-ridden, were some of the most exciting and rewarding of the trip. After wading back from the Temple of Literature on my first day, I planned out a few days of photographic edification. I started with the Women’s Museum, buried deep in the bureaucratic district of the city, between the American embassy and the river. There I found a fascinating exhibit on the wartime photographs of a general in the Vietnamese army. Next was an independent photo gallery connected to a print shop in central Hanoi, Kit Photography Gallery, Hang Trong, whose alleyway (pictured below) was a haven in the rain.

On my perambulatory journeys between these and other cultural institutions I was surprised that the gloom usually conferred by grey skies was nowhere to be found. Instead, the streets—now littered with fallen branches and sandbags—were filled with laughter, smiling children, and wild dogs with wagging tails. Elderly couples working together in street kitchens exchanged wry grins as they watched tourists stumble into deceptive potholes; the trash brigade, bedecked in blue and booming traditional Vietnamese songs into the dusk, scooped up sodden culinary detritus as they sung with seeming glee. This challenged the precepts of my meteorological philosophy – clearly, I had grown too accustomed to the depressing mimesis performed by Oxford students as they glance skyward in the dark depths of late Michaelmas.

[In the rain, a delivery driver picks up a package on Hai Ba Trung Street in Hanoi]

On the night of the 20th of July, smiles were wiped from faces as Hanoi’s metropolitan centre braced for the worst night of the storm. At a café I debated whether to stay another night and risk being landlocked, or flee northward just as the typhoon hit the city. Eventually, I was persuaded by a newly-befriended barista to leave the city. This turned out to be good advice, if I had stayed, I would have been stuck for four days.

I left that night on a sleeper bus bound for Cao Bang, the capital of the eponymous province and beating heart of that region’s booming agricultural economy. The region was once the seat of the Mac Dynasty, who presided over the northern tip of the country during the Middle Ages and locked it off from the Chinese Ming dynasty in the North and the Le dynasty in the South. Cut off from two key cultural and bureaucratic machines for hundreds of years, Cao Bang now lacks the infrastructure and heritage of its southerly neighbours, as well as the tourist crush which accompanies those qualities. For days I heard no English, saw no tourists, and ate exclusively local food (chicken feet included). Though photography galleries were few and far between, the surrounding countryside offered no shortage of spectacular compositions. Here is one such landscape, photographed from under an umbrella in the rain, and then again a few minutes later after the weather had cleared.

[Angel Eye Mountain, Cao Bang]

From Cao Bang I ventured west to Sapa, a tourist haunt famed for its picturesque, gradated rice paddies (as appear in the background of the picture below). After the relative calm of Cao Bang this was quite a change; indeed, a day in the throngs was enough for me. I decided to travel further west, where I stayed in a small farmhouse owned by a lady named La who taught me about the regional and linguistic variety of the area. I was her second guest, and she quickly set about challenging my faulted assumptions about the homogeneity of the landscape, language, and culture of the region, using her kitchen (and some Google Translate) to outline the particularities of traditional local cooking, and conjuring the most distinctive and satisfying dishes I have ever tasted.

[Pictures taken in a corn-growing district west of Sapa]

La explained that Northern Vietnam is composed of a great number of individual tribal cultures, each with their own language (not dialect, she was firm on this point), and with their own complex relationships with the land’s dynastic past. I had read a little about the tribal organisation of the country after becoming interested in one of Vietnam’s premier street photographers, Réhahn, who in 2011 set out to compile a portfolio of photographs of the country’s surviving tribal leaders, before setting up a museum with state funding which exhibited the portfolio alongside examples of traditional tribal dress. I decided that this would be the next item on the agenda, and after three days with La began the slow descent along the eastern coast to Hoi An, an old port town (and locus of the French military presence) where Réhahn’s galleries are located.

On the way, I stopped in Trang An, an aqueous region which had been struck particularly harshly by Storm Wipha. Here I visited the town’s heritage museums and hiked the local mountains and lakes, which have recently been listed as UNESCO world heritage sites. Pictures of this pitstop appear below.

[Trang An landscape complex and museum]

[View from Ngoa Long mountain]

When I arrived in Hoi An, the final stop on my tour, I visited two important photography galleries, both curated by Réhahn, and took a tour of the tribal heritage museum mentioned above. It was strange to see the broad span of cultures and languages which I had witnessed on my journey condensed into such a small space; I was urged to think about the tension in curatorial practices which require culture to be detached from its origins. On the other hand, this was not a Victorian expo, showcasing the bounty of an Imperial regime, but rather an attempt to protect and to preserve tribal cultures which survive in particular creative practices and media. This project was achieved through a careful arrangement of textiles, tools, and traditional dress according to a chronological and geographical framework which mapped the incremental shifts in process and technique between various tribes. This was a real highlight, helping me to contextualise the journey I had taken to Hoi An and putting more pressure on my assumptions about the homogeneity and unity of Vietnam’s national culture.

Against the unpredictable twists and turns of the trip I was encouraged to build a narrative thread in alignment with the contours of the country’s regional and topographic identities. At the end of my fortnight in Vietnam, I did not look back on an erratic adventure. In fact, I could easily trace a throughline from place to place, guided by a responsiveness to the world around me borne of necessity, and genuine worry about the storm. This emphasis on the natural world is not to hippify the experience, as it is easy to do on the tourist circuits of South-East Asia. Cleaving close to the countryside, as opposed to flying between touristy locales and relying on algorithms to direct me, was not intended as an appropriative attempt to mimic local life or to escape from my own culture. Indeed, quite selfishly, it was a pragmatic choice which helped me to stay safe in a storm I was not prepared for and to be a bit more considered about the kinds of photos I was taking. I was glad that the weather had challenged my ability to compile and catalogue in the style of a European gallery or expo, and pointed me in a more natural direction. In this way I could direct my attention away from gathering experiences and towards the people I met, like La; the gradual, tonal changes in the geography, language, and laughter I experienced along the way.

My exhibition will begin on December 5th in Common Ground on Little Clarendon Street. If you’d like to see a more cohesive portfolio, please do come and have a look!