The Laurence Binyon Prize: Tokyo Through the Lens

The Laurence Binyon Prize: Tokyo Through the Lens

By Damon Zuber, MSt in History of Art & Visual Culture(2024)

I had the privilege of traveling to Tokyo to explore photographic culture through the Laurence Binyon Prize, which offers one student each year the chance to study visual arts outside of Europe. I would like to sincerely thank the History of Art Committee for this extraordinary opportunity, and I highly encourage anyone with an interest to apply for the prize.

I hold the belief that photography is a particularly wondrous medium, existing in the liminal space between alchemy and science. I have distinct memories of watching an image reveal itself on a Polaroid for the first time in preschool, and remembered feeling that same magic once more after dropping my first contact sheet in the developer chemical bath in high school. As an undergraduate at Stanford, I had the opportunity to learn more about the underlying brilliance and innovation behind a photograph. In an analogue photography course, my professor provided a high-level overview of the reaction that takes place when the silver halide crystals in film are exposed to light. Meanwhile, a graphics class that I took through the Computer Science Department explored the mathematics and physics behind how the eye interprets light, principles which were then related to how the digital single-lens reflex camera was designed to try to mimic the function of the eye. At Oxford, I engaged with photographic images themselves, writing about theories and histories of photography in one of my Option papers and in my dissertation. There is perhaps no greater place in the world to explore the intersection of the technological and creatives sides of photography than Tokyo.

Tokyo is a hugely important city for the evolution of photographic equipment. The city plays host to the headquarters of Nikon, Canon, Fuji, Olympus, Pentax, Sigma, Sony, Mamiya, and more. These companies have fostered innovation across camera bodies, lenses and glass, film, dark room chemistry, and printing. On the artistic side, many incredible photographers have spent parts of their careers shooting in Tokyo, including Rinko Kawauchi, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Daidō Moriyama, and Shōji Ueda. The city is lush with photography-focused galleries and museums, and attracts enthusiasts worldwide to its many camera stores.

During my time in Tokyo, I stayed in Shinjuku. The ward plays host to the world’s busiest train station, which a staggering 3.5 million people pass through each day. Mere blocks from the station, there are countless camera shops, including the famed Kitamura Camera. The store features seven floors of all things photography, with an exhibition space in the basement. One floor had an extensive collection of rare Leica cameras, and another was devoted to “junk” cameras that one can buy to either refurbish or strip for parts. The store was any photographer’s dream, stocked with a seemingly limitless selection of camera bodies, lenses, and film stock. The walls also had fascinating displays of cameras and old photography magazines. I found myself inside several other camera stores in Tokyo, including a cramped basement with cameras essentially piled from the floor up to the ceiling.

I spent most of my days visiting some of the many photography-specific galleries sprawled throughout Tokyo. I started my exploration at Totem Pole Gallery, an artist-run space featuring an exhibition called a day on the planet by Ryoko Tomimura and Satoshi Wada. The images capture Tomimura’s family from her own perspective and Wada’s. The two photographers have been friends for years, but Tomimura and her family now live in the Netherlands. The series was captured during Tomimura’s trips with her children back to her native Japan. Wada’s photographs of Tomimura’s children are particularly interesting due to his relationship with his subject. While Wada and Tomimura share a strong friendship, Wada is a largely unfamiliar figure to Tomimura’s children. An untitled set of photographs features a young boy blowing bubbles outside, framed by an open door.

The doorframe separates photographer and subject, the former indoors and the latter outdoors. This separation tacitly establishes the photographer and the viewer as observers from afar, a careful non-interruption of the playing boy. The subject matter is intimate, yet Wada makes us feel distant.

I next had the chance to visit the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, where I saw two exhibitions. The first of these was Satoyama: Harmony with Nature and Resilience in Japan, a solo display of the works of the Japanese photographer Imamori Mitsuhiko. As the title suggests, the series featured photos of rural Japanese landscapes and the interactions and intersections between man and surroundings. The works were ordered by season, beginning in spring and ending in winter. Against the backdrop of natural beauty, Mitsuhiko captures moments of human obeisance and destruction. One photograph depicts a man bowing to a fish in hopes of a good bountiful season, while another shows a pile of trees chopped down by loggers. Unfortunately, photography was not permitted in the exhibition.

The second exhibition, The Resonance of Seeing, drew from works in the museum’s permanent collection, focusing on the abstract theme of reconciling the gaze of different perspectives, whether they come from the artist, the viewer, or the critic. Works were eclectic, spanning many decades and countries. There was an Anna Atkins cyanotype from the 1850s, Eugène Atget’s Pendant l'éclipse (1912), in addition to works by André Kertész, Bernice Abbott, Man Ray, and William Klein.

Though the display began with works by Western artists, the second half of the exhibition was largely devoted to images by Japanese and Chinese photographers, none of whom I had previously encountered. One photographer I was particularly fascinated by was Terada Mayumi. Her works are serene and simultaneously uncanny, capturing absence in various spaces. Mayumi’s framing of scenes creates a strong sense of depth, inviting the viewer to always look beyond the foreground. I was drawn to awning and oval table (2006), a scene that shows a table illuminated by natural light outdoors.

Mayumi captures the image from a dark room, with negative space enveloping much of the composition, heightening the distance between the table and the photographer. I personally found the stillness of the image to be eerie, as if the table were mere steps away, yet out of reach. Depth and absence once again appeared in Mayumi’s curtain 010402a (2001), where a white curtain billows in an empty room.

The movement of the curtain, the light shining through it, and the ensuing shadows assert the presence of strong sunlight and a breeze coming from outside, though the viewer does not catch a glimpse of the window or the outside world. The scene is enclosed. Beyond Mayumi, I enjoyed Sugiura Kunie’s photograms of tulips, which the artist created by placing flowers on photosensitive paper and exposing them to light.

Additionally, I found photographer Chen Wei’s process of image-making to be quite interesting. Wei comments on Chinese urban culture through scenes meticulously created in studio. One such photograph was New Station - if on a winter’s night (2020), which pictures abandoned luggage in front of a train platform, a nod to lockdowns throughout China at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the following days, I visited several photography galleries around Tokyo, starting with two of Taka Ishii’s locations. Though the gallery shows both Japanese and international photographers, the exhibitions that I saw both highlighted Japanese artists. The first presentation showed renowned photographer and critic Takuma Nakahira’s Overflow series, which stitched together images from the past 50 years that largely center around urban landscapes.

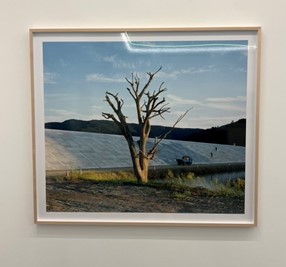

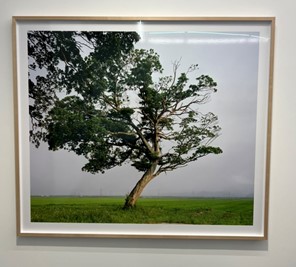

The installation of the photographs did well to encapsulate the feeling of ‘overflow,’ with images crowded next to one another, each jockeying for the viewer’s attention. The second Taka Ishii location I visited had Naoya Hatakeyama’s Tsunami Trees, a collection of photographs of trees in the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami that devastated parts of Japan. Hatakeyama’s compositions include the erection of a seawall, fallen branches,

I then ventured to Photo Gallery International, which began as a space to acquaint Japanese audiences with the works of photographers from the West Coast of the United States, but has since exhibited many Japanese photographers. The gallery was in the middle of setting up Yuki Shimizu’s Surfacing, but the staff kindly allowed me to walk around. Surfacing employs images and text to create fictional narratives about historical events in the Japanese town of Tateyama. Shimizu exposes her negatives to saltwater and sand prior to development, leading to unpredictable coloration and markings on her prints. Shimizu’s deliberate corrosion of her film underscores the artist’s own intervention in her storytelling. The images are much like memory – unreliable as ‘truth’ or ‘document,’ but rather embellished accounts from the artist’s own perspective and imagination.

While fortunate to see an exhibition at Photo Gallery International, I had less luck at MEM, a contemporary gallery that was between shows during my time in Tokyo. I was still delighted to peruse the extensive photography book collection at MEM. Similarly, Zen Foto Gallery was not exhibiting an artist when I visited. Instead, to mark the institution’s 10-year anniversary, the gallery displayed the 130 books it had published during its short history. The volumes amassed works from 80 photographers, mainly Japanese and Chinese.

In addition to having their corporate headquarters in Tokyo, Nikon, Canon, and Fujifilm all have associated galleries or museums to deepen their connection with the city’s photographic culture. The Nikon Museum was under renovation during my trip, but I was able to make it to the Ginza Canon Gallery and Fujifilm Photo History Museum. Ginza Canon Gallery plays host to two-week exhibitions of professional and amateur photographers alike. I had the chance to catch Susuke Miyata’s River, a collection of photographs of the diverse of forms of one river. These monochrome photographs reminded me a lot of Sumi-e blank ink paintings, with Miyata’s rivers resembling one continuous brushstroke on a white canvas.

The Fujifilm Photo History Museum, in contrast, focused on the evolution of photographic processes and equipment. Photographs were unfortunately not permitted, but the installation offered a dazzling display of cameras from as early as the late 19th century, as well as images taken by the camera models shown. The space also had the latest Fujifilm camera bodies, accompanied by text about recent breakthroughs in image resolution in their mirrorless cameras.

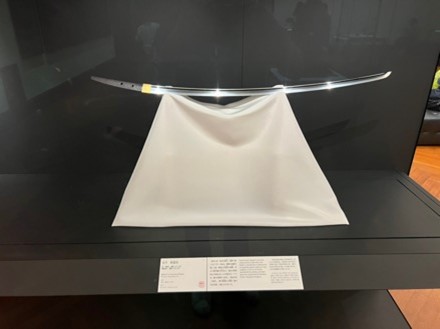

Tokyo offered countless adventures outside the world of photography. I paid visits to Sensō-ji, the oldest Buddhist temple in Tokyo, as well as Nezu Shrine, a Shinto Shrine built in the early 18th century. The city’s many gardens offered respite from the 40° heat, and I spent time in the East Gardens of the Imperial Palace, Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden, and Meiji Jingu Gaien outer gardens, which included a walkway lined with stunning gingko trees. A typhoon hit Tokyo during one of the days of my stay, so I took refuge in the Tokyo National Museum. I spent hours looking at kimonos, samurai armor, and centuries-old swords. My favorite piece in the museum was situated in the woodblock print section, Katsushika Hokusai’s Lilies (c.1833-34).

I ate street food in the alleyways of Omoide Yokocho, and made the trek to Toyosu Market, the largest wholesale fish market in the world, known for its early morning tuna auctions. I even had the chance to take part in the Shibuya Scramble Crossing, where as many as 3,000 people cross the street at once during red lights. Through it all, I had my 35mm SLR camera to document this unforgettable trip.

All photos by Damon Zuber